To add this web app to your homescreen, click on the "Share" icon

![]()

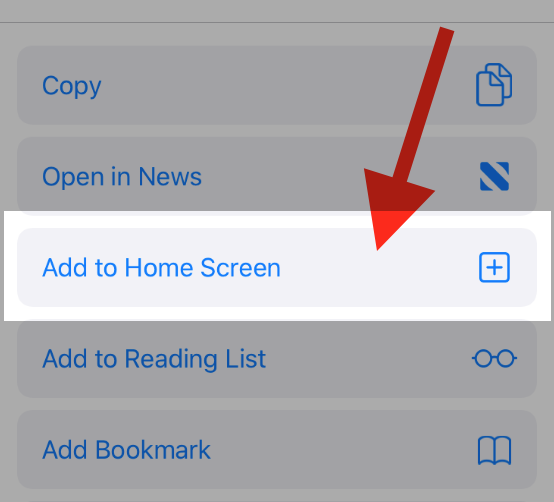

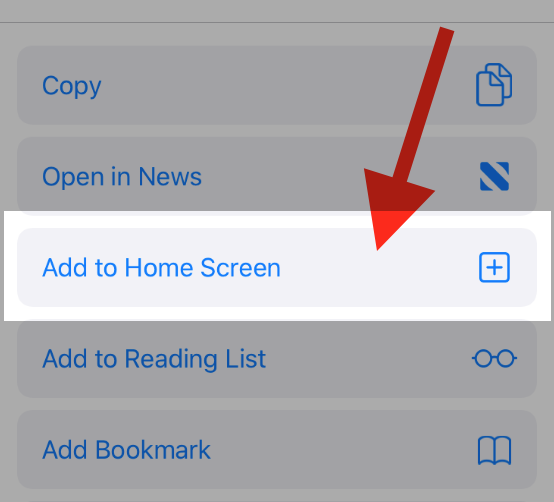

Then click on "Add to Home"

To add this web app to your homescreen, click on the "Share" icon

![]()

Then click on "Add to Home"

It looks like your browser doesn't natively support "Add To Homescreen", or you have disabled it (or maybe you have already added this web app to your applications?)

In any case, please check your browser options and information, thanks!

It looks like your browser doesn't natively support "Add To Homescreen", or you have disabled it (or maybe you have already added this web app to your applications?)

In any case, please check your browser options and information, thanks!